Understanding the

Meaning of Compassion

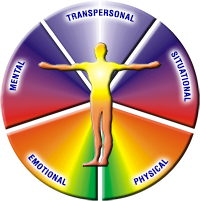

The Five Bodies

In working with compassion and the terms associated with it, we

incorporate the "five bodies" concept — a way of punctuating human existence so that we can better understand what it is to be a human being.

The "bodies" are the:

- Physical body — The physical manifestation of a person.

- Emotional body — The feeling nature of a person.

- Mental body — The creative and thinking nature of a person.

- Situational body — The physical, emotional, and mental milieu in which a person

exists. This body represents the circumstances in which one finds oneself.

- Transpersonal body — The profound, transcendent knowledge, aspirations and

beliefs of a person. Some people incorporate religious or other spiritual practice into the regimen for their transpersonal body (and, thus, is sometimes referred to as the "spiritual" body).

|

|

|

Each body communicates with and impacts the other bodies.

We often view "suffering" (refer to the discussion below) through the

lens of the five bodies (e.g., physical suffering, emotional suffering, etc.).

Compassion

Compassion — because it's a motivation — emanates from the emotional

and/or mental bodies. Compassion is sometimes confused with empathy, sympathy, pity, and charity. Its applications — compassion awareness, compassion bypass, compassionate action, and applied

compassion— can also be confusing. The definitions below may help to clarify the differences:

Professor Paul Gilbert provides an excellent (and concise) definition for compassion: a

"sensitivity to suffering in self and others with a commitment to try to alleviate and prevent it." 6

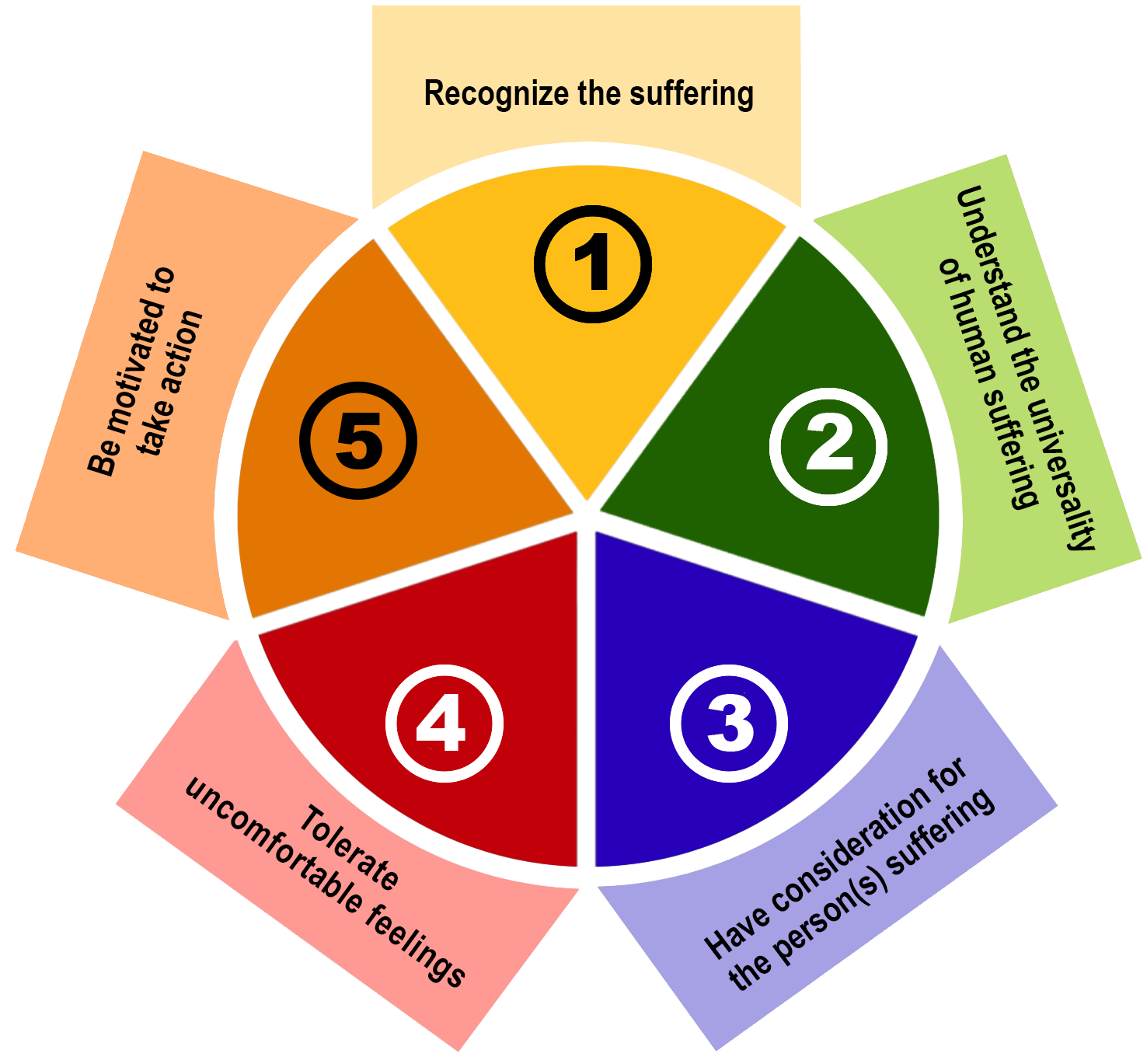

- Compassion — A motivation consisting of five elements:2

- Recognizing suffering.3

- Understanding the universality of human suffering.

- Consideration (emotional and or mental) for the person suffering.

- Tolerating uncomfortable feelings.

- Motivation to act to alleviate suffering.

This motivation can incorporate a feeling of deep sympathy and concern for one who is stricken by misfortune, accompanied by a strong desire to alleviate the suffering.4 The term compassion can refer to specific emotional responses focused on alleviating the suffering of others.5

- Compassion Requirements — Authentic compassion requires:

- Courage — The courage to take compassionate action, especially when it

presents difficulties.

- Commitment — The commitment to engage suffering, even when obstacles

are present.

- Competency — Having the requisite understanding and skills to

effectively take up compassionate action. These skills can be learned.

- Compassion Advocacy — The act of raising awareness about the nature and need

for compassion.

- Compassionate Action — Taking responsibility for alleviating and preventing

suffering experienced by sentient beings. There are three questions, which collectively answered in the positive, help confirm compassionate action:

- Does the act prevent or respond to suffering?

- Does the person exercising the compassionate act have an emotional and/or intellectual connection to the

suffering?

- Does the exercise of the compassionate act exact a price (physically, emotionally, mentally, situationally, and/or

transpersonally) upon the person exercising that act?

- Applied Compassion — The practice of employing compassion in specific cases as

part of the process to prevent or alleviate suffering.

- Compassion Fatigue — Exhaustion and emotional distress resulting from

compassion responses to overwhelming suffering, both in terms of frequency and intensity, experienced by others. Also known as vicarious or secondary suffering, it is a chronic experience of

assimilative compassion (refer to the discussion below).

- Assimilative and Nonassimilative Compassion — Two internal forms that

expressions of compassion can take.

- Assimilative Compassion — This form of compassion occurs when one takes on and internalizes the pain of

those who are suffering. This form of compassion is toxic and can expand the scope of the suffering to include those concerned about or attending to the person originally experiencing suffering. This

assumption can negatively impact the resolution of the original suffering and generate relational confusion. Assimilative compassion is also a strategy to shift attention from someone who is

suffering and transferring the focus to one's self.

- Nonassimilative Compassion — Those who engage in nonassimilative compassion feel for the suffering of

others but recognize that the pain they see is not theirs. They can then fully engage in supporting those in pain without adding to scope of that suffering.

- Compassion Aversion — A condition in which a person has developed a resistance

to compassionate treatment from the self or others. The condition is characterized by an inability to deal with compassionate responses to suffering due to psychological stress, feelings of being

overwhelmed (flooding), sense of worthlessness, disbelief, or suspicion. Attempts to continue exercising compassionate behavior can aggravate the condition. The application of compassion must be

adjusted to meet the ability of the person who is suffering.

- Compassion Bypass — A form of self-gratification in which one considers

compassion in terms of how it can benefit them or their interests, including their self-esteem. Compassion bypass is a form of moral self-licensing and, at times, the "strategic pursuit of moral credentials." Some of the characteristics of compassion bypass are:

- A misinterpretation (often innocent) of what constitutes compassion.

- Acts which are confused with pity, charity, being nice, etc. — all of which are part of a greater constellation of

caring behaviors that can be valid but are not "compassion."

- Creating an appearance of compassion to avoid the courage, commitment, and competency required for meaningful

compassionate action.

- The absence of humility (e.g., focusing on becoming "compassion celebrities" or "compassion stars"). Collective and

self-congratulatory behaviors (e.g., “celebrating ourselves for our compassionate deeds” at a gathering) fall within this category.

- The need for physical, emotional, mental, social, or transcendent pay-off (not to be confused with

rewards that come naturally and without demand or expectation). This characteristic is sometimes used as a strategy for self-promotion.

- "Keeping score" of one's compassionate actions to impress one's self and others with one's compassionate deeds.

- The absence of emotional or intellectual commitment in the act.

- The focus on single, self-gratifying acts for which one has little investment.

- Claiming compassion when engaging in acts that do nothing to directly alleviate suffering.

- Dodging the messy work often demanded by compassion, such as extending compassion to those one finds disdainful (e.g.,

those with differing political beliefs, those who have engaged in destructive behavior).

- An unwillingness or inability to tolerate uncomfortable feelings that accompany deep compassion work.

- Empathy — The intellectual identification with or vicarious experiencing of the

feelings, thoughts, or attitudes of another. Empathy incorporates cognitive elements that allow us to see through the eyes of others and to value their welfare.3 Since it is a skill (not an emotion or motivation), it can also be used maliciously. Used in a caring way, empathy is

the first step in engaging compassion, pity, or charity. It is an interpersonal attunement that can connect one person of another's joy, excitement, setbacks, and suffering. When suffering is

involved, empathy is the gateway to compassion: the first step to the compassion experience.

- Sympathy — The fact or power of sharing the feelings of another, especially in

sorrow or trouble.

- Pity — Sympathetic or kindly sorrow evoked by the suffering, distress, or

misfortune of another, often leading one to give relief or aid or to show mercy.

- Charity — Generous actions or donations to aid the poor, ill, or helpless.

Suffering

We categorize suffering in three degrees of severity:

- Necessary Suffering — Painful experiences that are not directly health

or life-threating. For example, when a young child learns that they are not allowed to take a toy away from another child, they may experience loss, disappointment, and hurt. This is, indeed,

suffering, but it is also part of the child's learning. Such lessons are essential to building depth and resiliency. For adults, first degree suffering can take the form of loss of a loved one, the

pains of aging, uncertainty, and other common experiences that come with one's existence. Although necessary, the experience still merits compassion.

- Non-crippling or Non-fatal Suffering — These painful experiences

consist of anxiety, stress, despair, illness, injury, or loss that does not cripple or threaten life. Examples are divorce, job loss, temporary sickness, indebtedness, intolerance, shaming,

injustice, and exploitation.

- Crippling or Suffering that Risks Death — The most severe form of

suffering, this category includes experiences such as crippling injuries or diseases, severe physical and/or emotional trauma, starvation, social group extermination, aggravated assault, murder,

fatal exposure to the elements, and fatal diseases and injuries.

The challenge of suffering includes, but is not limited to, endemic rage,

racism, corporate exploitation, intimidation, terrorism, hate, intolerance, human trafficking, assaults on women, suicides, torture, political corruption, bigotry, shaming, child abuse, debt slavery,

demonizing, rancor, homelessness, bullying, extreme income inequality, manufactured fear, pollution, injustice, and despair.

Organizational

The International Center's focus is on organizations and we look at suffering that directly occurs within those social systems. Among the forms suffering takes are:

| |

- Bullying

- Intimidation

- Discounting

- Humiliation

- Threats

- Miscommunication

- Envy

- Jealousy

- Resentment

- Impatience

- Incivility

|

- Poor communication

- Misunderstanding

- Unfairness

- Favoritism

- Discrimination

- Insufficient pay and benefits

- Domination by managers

- Excessively heavy workloads

|

- Drudgery

- Lack of inclusion

- Disrespect

- Loss of purpose

- Meaninglessness

- Poor working conditions

- Insincerity

- Insufficient mental challenges

|

Individual

Individual, family, racial, and other forms of suffering that impact organizations are also important and is addressed by the International Center. Some statistics indicate the importance of this

phenomena:

- In the United States, an estimated 35% of adults are in collection for defaulting on their

credit.

- With the economic meltdown in the last decade, 8,8 million people lost their jobs and 1.2 million

lost their homes.

- About one in eight American’s were abused as children.

- Research suggests that 350 million people worldwide struggle with depression.

- A report by the London School of Economics and Political Science at King’s College London estimates

that depressed employees cost European businesses €96 billion (£77 billion, US $129 billion).

- The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that more than 700,000 people die from suicide each year.

- WHO also reports that, in the last 45 years, suicide rates have increased by 60% worldwide. Suicide

is now among the three leading causes of death among those aged 15-44 (male and female).

- In 2012, there were a total of 2,044,270 reported incidents of crime against women in India.

- African-Americans comprise 13% of the U.S. population and 14% of the monthly drug users, but 37% of

the people arrested for drug-related offenses in America.

- In the United States, 1 in 4 women and 1 in 6 men will be sexually assaulted before the age of

18.

- In the United Kingdom, 200,000 Muslims who turn away from their faith are faced with abuse,

violence and even murder.

Those in the grips of this suffering lead, work, volunteer for, or

otherwise participate in organizations. People struggling with the loss of their job or home, a death in the family, chronic illness, threats from bill collectors, violent crime, discrimination,

failure, a devastating childhood and/or experiencing a bleak existence will deal with workplace challenges differently than those who are not plagued by similar torment. Recognizing and and

responding to organizational and personal suffering is an important element in moving organizations toward greater ethical, financial, and sustainable success.

Notes

|

1. |

Much of the

material for this page is taken from the book (in development), Compassion and the Alchemy of Being, by Ari Cowan. Reproduced with permission. |

|

2. |

Strauss, C., Taylor, B.L., Gu, J., Kuyken, W., Baer, R., Jones, F. & Cavanagh, K., What is Compassion and How Can We Measure it?

A Review of Definitions and Measures, Clinical Psychology Review (2016), doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2016.05.004 |

|

3. |

DeSteno, D. (2015). Compassion and altruism: How our minds determine who is worthy of help. Current Opinion in Behavioral

Sciences, 3, 80–83. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2015.02.002; Goetz, J. L., Keltner, D., & Simon-Thomas, E. (2010). Compassion: An evolutionary analysis and empirical

review. Psychological Bulletin 136, 351–374. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0018807 |

|

4. |

For a further discussion on compassion, see Lim, Daniel & DeSteno, David (2016). Suffering and Compassion: The Links Among

Adverse Life Experiences, Empathy, Compassion, and Prosocial Behavior. Emotion, 16, 175-182. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/emo0000144 |

|

5. |

Condon, P., & Feldman Barrett, L. (2013). Conceptualizing and experiencing

compassion. Emotion, 13, 817–821. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0033747 |

|

6. |

Gilbert, P. (2017). Compassion: Definitions and Controversies. In: P. Gilbert (Ed). Compassion: Concepts, Research and Applications. (p. 3-15). London: Routledge, page 11 |

|